As a traumatic brain injury survivor, watching my home team win Super Bowl 50 was incredibly conflicting.

Growing up in the beautiful mountains of Boulder, Colorado, I was an active child, a young athlete, and have been rooting for the Denver Broncos as long as I can remember. I’m native to a state that bleeds orange and blue so heavily, we felt it appropriate to intimidate newcomers with a terrifying, red-eyed, Bronco statue outside our major airport. So It’s easy to imagine the sense of excitement we Coloradans experienced watching our beloved donkeys win the Fiftieth Super Bowl last Sunday.

However, my life changed almost five years ago when I fell two stories and landed in a 12-day coma with less than a 10% chance of recovery. I spent many months re-learning to walk, talk, eat, and think clearly. And though I’m no longer able to be the athlete I once was, I haven’t lost any appreciation for the many economic, social, and health benefits sports can bring about. In fact, working in the brain injury community has brought me even closer to the kind of mental, physical, and emotional struggle athletes endure to do what they do.

However, my life changed almost five years ago when I fell two stories and landed in a 12-day coma with less than a 10% chance of recovery. I spent many months re-learning to walk, talk, eat, and think clearly. And though I’m no longer able to be the athlete I once was, I haven’t lost any appreciation for the many economic, social, and health benefits sports can bring about. In fact, working in the brain injury community has brought me even closer to the kind of mental, physical, and emotional struggle athletes endure to do what they do.

And while I’ve always loved watching football, this year’s game was different. Not because it was my home team in a memorable fiftieth championship game… Not because we were all fearing this would be a repeat disaster of the last time the Broncos went to the Super Bowl… Not because, statistically, this was one of the worst Super Bowl wins in history… Not even because of Payton Manning’s cringe-worthy use of sponsor promotion in three of his post-game interviews…

This year’s game was so conflicting because my work in the brain injury community has shown me the science behind the cumulative effects of each and every knock to the head, the corporate cover-up of an inconvenient truth, and the one word on everyone’s mind: “Concussion.”

Headliner

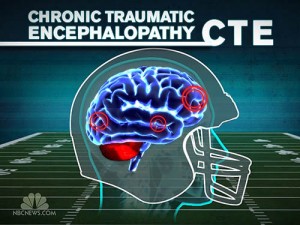

Ever since Dr. Bennett Omalu‘s discovery of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (C.T.E) in the brain of deceased hall-of-famer Mike Webster, the word “concussion” has become increasingly synonymous with the NFL. It continues to be the focus of special reports, mini-docs, and nightly news headlines, even landing on “the big screen” in this year’s film “Concussion” starring Will Smith as Omalu himself.

Ultimately, the NFL has failed in it’s attempt to smear and discredit Dr. Omalu and his discovery, and the organization’s unwillingness and incompetency to educate and protect both players and the public about the concussion epidemic in contact sports is borderline criminal. Thankfully, those paying attention aren’t quieting down, and one need only see what’s trending on social media the past few weeks to grasp the broader picture.

This season, we saw NFL great Ken Stabler‘s family speak out about his struggle with C.T.E and Vikings quarterback Joe Kapp (Alzheimer’s) planning to donate his brain for concussion research. Local news gave a casual report about former Broncos seeking help for “the brain injuries they suffered during their playing days.” We watched pro wrestling icon Daniel Bryan speak candidly with his audience about an inability to keep wrestling after “a lot of concussions.” And let’s not forget the time Brett Favre opened up about the “toll” football has taken on his life and his corresponding loss of memory.

Even The Onion joked about the “Super Bowl Confetti Made Entirely From Shredded Concussion Studies.” The broadening spotlight on head-trauma in sports is not going anywhere and for good reason.

Postgame Stats

If you’re standing, take a knee.

Recently, researchers with the Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University found C.T.E in 96% of the NFL players they examined and in 79 percent of all football players. “In total, the lab has found C.T.E in the brain tissue in 131 out of 165 individuals who, before their deaths, played football either professionally, semi-professionally, in college or in high school.”

And C.T.E isn’t just manifesting in aging NFL retirees, as demonstrated by the post-mortem examinations of twenty-something NFL pros Tyler Sash and Adrian Robinson. It’s showing up in the brains and behaviors of players from all kinds of contact sports. In our interview with Dr. Unini Odama on the concussion crisis, we we’re reminded that some 25% of high school players show signs of C.T.E.

We’re talking about the sum of many thousands of otherwise “normal hits”

So while the CDC estimates 1.7 million individuals suffer a TBI in the United States each year, we now know that number to be just the very tip of the iceberg. Not only is that statistic limited to reported cases, but it doesn’t take into account recent findings about prevalence of C.T.E in contact sports. The public’s lacking awareness about brain injury is so vast that many people have no idea what a concussion is or how to report one….that it’s not just about losing consciousness…or that a “concussion” is a brain injury.

Here’s the kicker: not only is head trauma extremely prevalent in contact sports, it’s the type of repetitive head trauma that makes all the difference. To make this absolutely clear, C.T.E is not only about how many times a player “gets their bell rung” or loses consciousness on the field. We’re talking about the sum of many thousands of otherwise “normal hits” players experience during their careers, which cause the brain to endure nearly undetectable micro-concussions from bouncing around inside the skull.

Worse, C.T.E is an entirely different animal compared to other kinds of neurodegenerative diseases. In many cases, C.T.E manifests itself through noticeable behavioral and emotional changes, such as aggressive and suicidal tendencies, as shown in the deaths of a number of former players. Dr. Omalu himself said he “would bet his medical license” that C.T.E is at least an influence–if not the cause–of the erratic and aggressive behavior in O.J. Simpson.

A New Playbook

So what’s the next play?

Do we demand safer and better helmets? As we learned from our talk with neurobiologist Peggy Mason, better helmets will not solve the problem. In fact, helmets were designed to protect players from skull fracture. While they can help protect players from linear impacts (direct impact with little to no neck movement), they do nothing for rotational impacts (the head whipping around), which end up being at the source of the worst kinds of head trauma.

Should we just be afraid of athletics, head indoors, and pull our kids out of sports programs? I don’t think fear is necessarily the answer either. The truth we all know is that accidents happen anywhere and anytime. Many of the survivors I’ve met and speak with experienced a single injury while going about their daily lives. And, of course, no one signs up expecting a brain injury.

I think the best answer is to be smart as opposed to scared. Learn about the nature of brain injury, make informed decisions, assess risks, and ask yourself if the risk is worth the reward. We owe it to our kids, our brains, and our future to make sure we inform and protect each other.

So let’s be honest with ourselves: It’s demonstrably clear that playing football poses a serious risk to the brain. And with 96% of NFL players showing C.T.E, I don’t believe it’s a worthwhile risk for children to take. Especially when most legal tackles in football are perfectly framed for rotational impacts. There are counter-arguments such as the claim that extreme sports like skateboarding or surfing may be more dangerous, but they demonstrate a lack of awareness about the science of head injury and the nature in which repetitive micro-concussions lead to C.T.E.

The End Zone

Football is America’s favorite sport. The Super Bowl is the most watched program of the year. It seems safe to say that the sport is here to stay. Still, we’re seeing an increasing number of parents, former coaches, and even President Obama openly saying that they wouldn’t let their own children play football. And you can’t blame them.

That’s the very statement the NFL doesn’t want you to hear. But this is their new inconvenient truth, mirroring our nation’s tobacco predicament 45 years ago: we are a nation of newly-informed and concerned smokers, and they are Big Tobacco. And the NFL has certainly played the role well: smearing Omalu and denying the science, paying off financial settlements (which make exclusions for C.T.E), and skirting real change, while hyping their “unfaltering commitment to better research, equipment, and guidelines.”

As Dr. Omalu wrote about kids and football in a recent op-ed for The New York Times:

“Knowing what we know now, we do not smoke in enclosed public spaces like airplanes; we have passed laws to keep children from smoking or drinking alcohol, and we do not use asbestos as an industrial product.

As we become more intellectually sophisticated and advanced, with greater and broader access to information and knowledge, we have given up old practices in the name of safety and progress. That is, except when it comes to sports.”

Again, he’s right on the mark. And he’s not alone in his campaign for protecting children’s brains, but we need to do more. We can’t take our eyes off the ball. We need better awareness, more comprehensive education, rules, regulations, and protection for youth and school sports. As long as football remains business as usual, our brains will continue to lose.

Helmet Graphic photo credit: NBCnews.com

Join our newsletter and download my free eBook!

“My TBI Story” is an overview of the events leading up to my severe traumatic brain injury, the many stages of my recovery, and the road my life has taken since. I’ve included a short FAQ with insights to the recovery process and a list of useful links.

8 Comments

Leave your reply.