My half flaccid and half spastic body was transferred to a cot. I was wheeled out of the room, down the hall until we reached the elevators that my friends and family had used for 6 weeks.

The doors opened and I was wheeled through the lobby. The vibrant colors shined in the sunlight as we exited the building onto the street. Until this moment I had not been outside with the sun in 44 days. The back doors of an ambulance transport swung open, and I was lifted into the vehicle.

Everything was surreal. I felt like I was going to throw up as the scene started to spin. Motion Sickness is often caused from a mismatch between the vestibular and visual systems. Both of these systems are filtered through the cerebellum. I had hardly moved at all in over 6 weeks, my cerebellum was damaged, and I was now in stop and go traffic traveling to Manhattan over the Queensboro Bridge.

Riding along the east side of Central Park, we arrived at Mount Sinai’s Klingenstein Center. I was lifted out of the ambulance and wheeled through the hospital doors, up the elevator to the TBI Ward, and into the room that had been prepared for me.

This was a room for one patient, a luxury afforded to me because of my previous diagnosis of MRSA. The room was clean and pristine and the lighting felt bright and open. A mix of tubes, devices, and monitors hugged one side of the bed. A grouping of heart-shaped balloons reading “I Love You!” bounced against the window overlooking Central Park. Little did I know, this room would become home for the next three months.

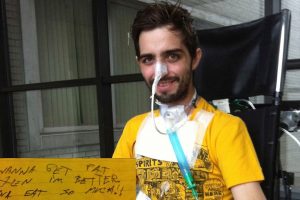

“Hi, Bubba!” A voice sang. “Nice digs!” My former-girlfriend nodded her head with approval. My awareness was numbed as my eyes floated like dolls eyes. Again, I couldn’t walk or eat. My hand was in “the claw” position, my foot in “the ballerina” position (drop foot), I had a foley catheter to collect my urine, and I had an NG (nasogastric) tube sticking out of my nose. When I look at pictures and videos of myself during this time, I am unable to recognize the confused man pictured with wondering eyes.

A doctor entered the room. “You must be Cavin.” He said, pronouncing my uncommon name correctly. Then, looking to my mother, he said “and this must be your sister?”

“Oooo… you… are… smooth” I replied in a raspy voice, as I weakly extended my limp arm to him. He smiled as he shook my buckled limb like a noodle.

“You’re going to do just fine here.” He introduced himself as Dr. Brian Greenwald, the Medical Director of Brain Injury Rehabilitation at this hospital. “So what are your goals here?” he asked.

Hungry, and emaciated, my words crumbled before they exited my mouth, “Eat… food… No… tubes.”

He smiled. “We’re in the business of removing tubes, not putting them in.”

While this was music to my ears, it did not turn out to be the case. What none of us knew at that point, was that the narrowing in my throat that cause breathing problems before was still there…

It had only shrunk the stenosis temporarily.

This would become painfully clear the next day.

Can you relate to some of this? Does it bring back some memories?

When working with loved ones of survivors who are being transitioned to a new environment, I have found that it makes a huge difference to bring some familiarity with them. This helps to set the stage of their new scenario and can help to not only jog their memory, but also to provide some comfort during an uncomfortable time.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.